According to data released by the Office for Students, there are significant disparities in performance between universities and topics.

According to data supplied by the Office for Students (OfS), the proportion of students in England who secure graduate-level jobs varies substantially between universities and disciplines studied, which is likely to fuel the government’s efforts to restrict admittance to “low-quality” courses.

Imperial College London graduates were the most likely to finish their studies and pursue a professional career or further education, with 92 percent doing so a year after graduation. raduates of the Royal College of Music and Oxbridge came in second and third, respectively.

On the other hand, less than half of degree holders from a number of well-known universities do the same.

According to the Office for Students, only a third of graduates from the University of Bedfordshire are employed or pursuing further education.

“This government has a manifesto pledge to combat low-quality higher education and drive up standards, and this data demonstrates there is much more work to be done,” Gavin Williamson, the education secretary, said.

“Our historic skills law clarifies the Office for Students’ capacity to take much-needed action in this area, including enforcing minimum criteria for institutions on course completion rates and graduate outcomes, and I eagerly await the results of this work.”

The higher education regulator’s estimates are based on data from students who graduated in 2018-19, with dropout rates from the previous year and their employment status 15 months after graduation factored in. Those who continue their education or leave the workforce for a variety of reasons are also counted.

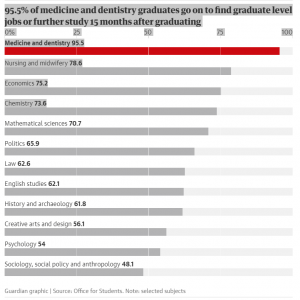

Medicine, dentistry, and nursing, as well as veterinary sciences and economics, topped the list of topics that were most successful in getting students into graduate school. Graduates with a political science degree were more popular than those with a law degree. However, the OfS authorised fewer than half of students who took sociology, social policy, or anthropological courses.

The data showed “dramatic disparities” in outcomes depending on where students study and what they study, according to Nicola Dandridge, the OfS’s chief executive. “While we have no plans to use this measure for regulatory purposes,” Dandridge added, “we are determined to combat poor quality provision that gives people a bad deal.”

Many of the subjects at particular universities were too small to yield reliable findings. But among those who did, medicine and dental degrees at several universities had success rates of over 95%, with only graduates in economics and maths at Oxford interrupting the trend.

Universities that recruit students from underprivileged backgrounds, who are less likely to complete their degrees, are penalised, according to critics of the OfS numbers. Just 15% of students enrolled in the University of Bedfordshire’s business and management programmes achieved graduate-level achievements, and only a quarter of those who enrolled went on to graduate.

The data are also likely to skew the outcomes for graduates in fields like the creative arts, where freelancing or temporary work is significantly more common in the early stages of their careers.

The research also revealed that the university attended had a greater influence than the subject studied in many circumstances. Only 59 percent of students completing identical courses at the University of Southampton fulfilled the job criteria after graduation, compared to 85 percent of Oxford philosophy and religious studies graduates.

Other shocks emerged from the OfS tables: the University of Bath outperformed numerous members of the Russell Group of research universities, including Durham, Bristol, and Exeter.

Source: The Guardian ( https://www.theguardian.com/education/2021/may/19/job-prospects-vary-widely-for-graduates-in-england-data-shows ).